As teachers, probably the majority of our classes are perfectly fine. Nothing extraordinary; nothing terrible. But occasionally we have that really awful class that practically sends us home in tears, no matter how many years we've been teaching. And then, at times, we teach a nearly perfect class. One that just feels right. One where it all comes together.

I do think it's important to write about the classes that go poorly and to consider what went wrong and what we might do in the future to make them better (I wrote about one of these classes for me this year here.) It's also important that we document the classes where we mix the right elements together and the class seems to resonate for us and the students. Below I'll describe a class where everything seemed to work, and I'll analyze some of the distinct elements that made this class unique.

Context. Throughout the semester in this intermediate-level English class we'd been exploring the theme of "love." We began with selections from Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses and talked about the concept of "eternal love." Then we moved on to a short story "Wedding Night" by Tom Hawkins looking at the idea of "unrequited love" which led us to a Def Poetry Jam poet Maya Del Valle's "Seduce Me" and the idea of "passionate love." In the two most recent classes, we read William Saroyan's short story "Gaston" and we began to discuss the theme of "familial love."

Turning the Text. We sometimes read literature to better reflect on our own lives. Louise Rosenblatt explains that:

The reader seeks to participate in another's vision--to reap knowledge of the world, to fathom the resources of the human spirit, to gain insights that will make his own life more comprehensible.

From my own background in studying literature, I do appreciate the analytical teaching approach -- examining structures, character development, or language in a formal way -- yet the academic side of literary studies was never as appealing to me. I've always been more interested in making literature a vital part of the community. After college I did this by directing plays and later by bringing literature "from the page to the stage" at the ArtsLiteracy Project. Now I do it in a very different way.

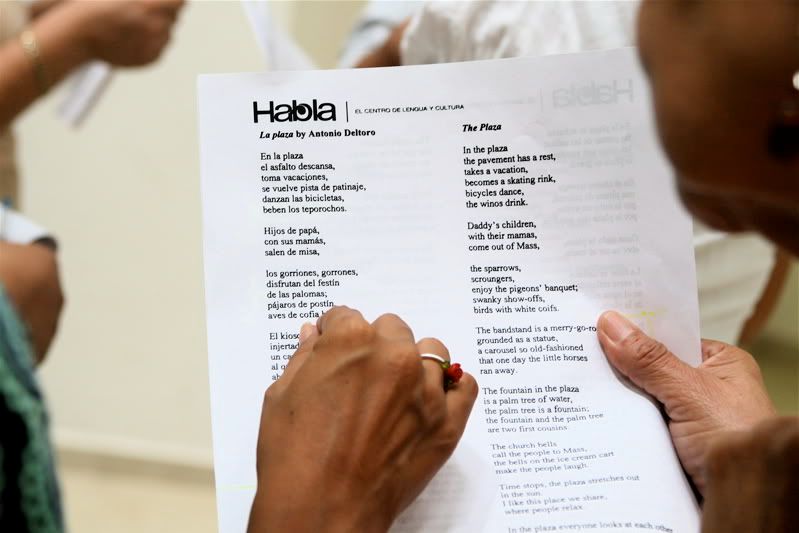

My students who come to my classroom at night spend the day occupied in a variety of professions. They are lawyers, teachers, social workers, psychologists, doctors, and bankers. The last thing they want to do after work at 8:00pm is analyze a work of literature, perhaps the same way they did in college. They come at night, of course, to learn English. But they also come to meet other people from the community. They come to chat, tell stories, and learn about their fellow students who grew up in the same community. They do come to read literature to, in Rosenblatt's words, "fathom the resources of the human spirit." Sometimes we take the time to work through a poem, word by word and line by line. Always after reading a text we talk about the essential ideas. Usually I ask a simple broad question like, "What did you find interesting? What was a moment that jumped out for you? Was there a particular line or passage you found compelling?" From these questions we delve into deeper conversations about the story and the characters. After reading the story I turn the text towards the lives of the students, meaning, we use the text as inspiration to tell our own stories, write poetry, or create through a variety of artistic mediums.

Everyone Talks. The students entered the classroom at 8:00pm, tired from a full day's work. When I'm working with a group of people, whether I'm teaching, running a meeting, or leading a workshop, I always begin with a question or activity that asks each person in the room to say something substantial. I avoid gimmicky prompts like, "Describe your day as a color" but instead ask a question that relates to the theme we are discussing in the class or the topic we will be exploring in a meeting. I do this because it sends the message that I will not be the one dispensing information and lecturing during the class. The classroom environment is a democratic space, and I find that when everyone talks immediately when the class begins, they are more ready to participate throughout the entire class. In the previous classes we had read and discussed "Gaston." The goal of this class was for students to talk about their own lives in relation to the text. Since "Gaston" is about the relationship between and father and his daughter, I wrote the question on the board, "What is one of the favorite things you did with your father or mother?" I placed everyone in pairs and asked them to tell their story. I told the partners to listen intently and ask many questions. The class began with pairs intently telling stories.

Shifting Spaces. Our classes are ninety minutes. Since we could set our own schedule, we experimented with different class lengths and found a ninety minute class is the perfect length of time to delve deeply into a given subject. Many schools have forty-five minute periods which, after the class gets settled and you go over business, only allows for about thirty minutes of instruction. We found that even an hour wasn't long enough: the class ended when we felt we were really beginning to get into our groove. Even though ninety minutes feels like the ideal amount of time, it does require several different pedagogical moves, from one activity to the next or even from one space to another. For this class, after the students arrived and told their initial stories, we moved to a new physical space, one that was completely free of tables and chairs.

Everyone Performs. Since this class was new to performing, I began with an easy activity, one in which each person offered a little "performance." In the empty space I placed the group in the circle. I asked everyone to think of a phrase "your father or mother used to say to you over and over again." I modeled, "Kurt, clean up your room!" and asked everyone to repeat after me with the same emotion and pitch. Usually in the English class we only speak in English, but today I told them since their parents spoke to them in Spanish they could use Spanish. We quickly went around the circle, each person speaking their line, and everyone else energetically repeating. I then asked them to translate their lines into English, and we repeated the activity in a different language. (This activity was based on one called Lines from Childhood originally developed by theater educator Jan Mandell. Click on any of the activity names to see the full descriptions on the ArtsLiteracy Project's website).

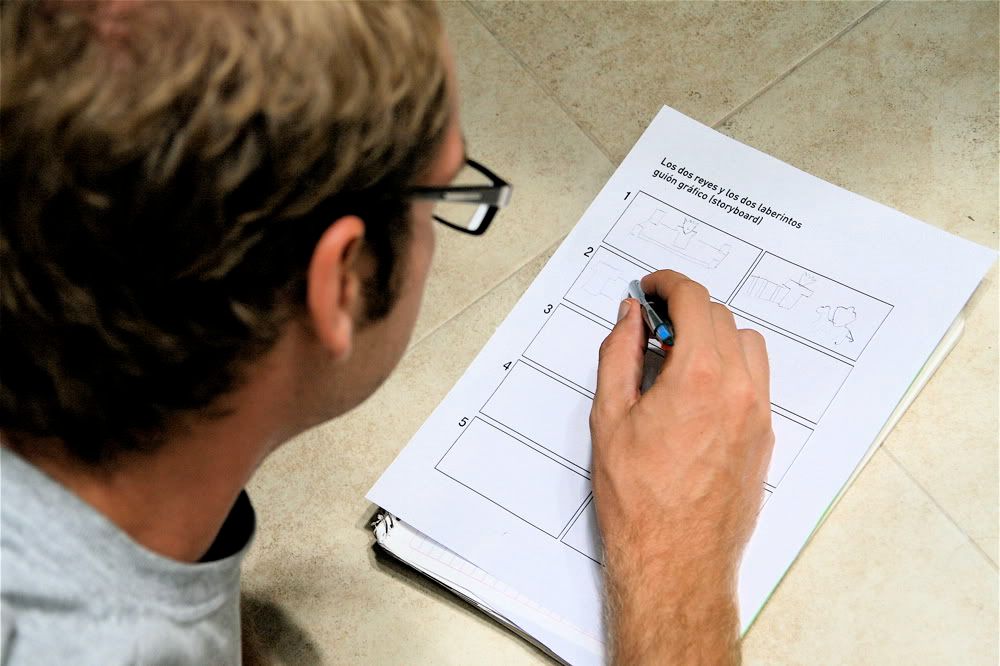

Create. In pairs, the students then participated in an activity called Sculpture Garden. In Sculpture Garden one student is the "sculptor" and the other student is the "clay." I gave them an instruction like, "Create a sculpture of yourself as a child," and then the sculptor would form their partner into a sculpture. In two minutes, the room was filled with sculptures of children. We moved around the room and the sculptors described their own interpretations of themselves. We continued with prompts, "Create a sculpture of yourself as a teenager. Create a sculpture that represents your mother . . . your father."

Intense Speaking and Listening. The final "performace" of the class is roughly based on Brazilian theater director Augusto Boal's activity Pilot/Co-Pilot. I asked everyone to sit on the floor, back-to-back. I turned out the lights and explained, "Choose person A and person B. Now, person A will tell person B about their mother or father. It can be any kind of story, perhaps a funny story, or maybe a sad story. When I say 'Go!' person A will begin telling their story and will keep telling it until I say stop. If you stop early, go back and add more details, tell us about the context. During this time, person B needs to be completely quiet, only listening. You need to listen as if your partner is the most important person in the world. After we're done, person B will need to tell the same story back to person A so listen intently and try to remember as many details as possible." We began and the room filled with the sound of stories being told. After about five minutes, we stopped and then person B had to tell the story back, in the first person. In other words, they became their partners, retelling the same stories back to them. We switched partners and then the Bs told their stories and the As repeated the stories back.

Those are the details, but here are the broader ideas worth remembering:

- the importance of literature. The stories that my students told would not have been as rich if we hadn't begun first with "Gaston." The text allowed us to, as Rosenblatt notes, "gain insights" into our own lives which, in turn, lead to richer experiences when we tell our own stories.

- everyone talks, everyone performs. There wasn't a moment during this class when students weren't engaged deeply as a speaker, listener, or performer. As a teacher I never stood in front of the class. Instead I was a facilitator providing the instructions and prompts to inspire their responses.

- multiple moves. We changed activities and spaces many times during the ninety minutes. The students also changed groupings several times working first in pairs, then as a class in a circle, then again in pairs, then in small groups, and then ending the class in pairs.

- displacement. During the sculpture garden, students transformed into their partners as a child or as a teenager. Similarly, during pilot/co-pilot, the listener becomes the speaker retelling the story back in first person. The students were seeing versions of themselves in the other person, a process we refer to as displacement.

Perhaps the most important foundation of the class was the authenticity of language. All of the communication in the class was real. The students didn't fill out worksheets or take practice tests. They didn't answer multiple choice or true false questions. They told meaningful stories about their lives and listened to the other students. This is what the founder of Highlander Myles Horton refers to when he talks about literacy programs he began during the Civil Rights era called Citizen Schools. The literacy programs he explains, "had a purpose but reading and writing wasn't the purpose. Being a citizen was the purpose." I thought of this line when one of my students wrote about our class:

Habla me ha enseñado ha disfrutar la experiencia de formar lazos en un espacio común pura un grupo y ¨el aprendizaje de la lengua inglés¨es como un plus.

I have enjoyed the experience of forming ties with my class in a shared space. "To learn the English language" is a bonus.

We learn a language to expand our lives and broaden our community. The classroom is a safe space to begin using language to reach out beyond ourselves to tell our stories and even more importantly to "listen as if that other person is the most important person in the world."

In Providence, Rhode Island, a group of colleagues and I started the ArtsLiteracy Project, an organization that explored ways of teaching reading and writing primarily through performance. We partnered directors and performers from local theatres with English and language teachers in schools, and together we developed a methodology for using performance to teach reading.

In Providence, Rhode Island, a group of colleagues and I started the ArtsLiteracy Project, an organization that explored ways of teaching reading and writing primarily through performance. We partnered directors and performers from local theatres with English and language teachers in schools, and together we developed a methodology for using performance to teach reading.

When I first started teaching literature, I felt I needed to cover all the important material in a book. Before class, I would read through the chapters I had assigned my students looking for key symbols, descriptions, or dialogue, and then in class that day I would be sure we properly made our way through all the moments of the book I deemed important. Like most teachers, at some point along the journey, I realized how vital it is to hand this work over to the students. The first selfish reason being that if I only give the students everything I know I'm not growing; I'm not learning from what they have to offer. Secondly, we also know that the cognitive wrestling is where the learning takes place. If we are doing all the smart stuff before we get into the classroom, what is left for the students? And are we teachers really that smart?

When I first started teaching literature, I felt I needed to cover all the important material in a book. Before class, I would read through the chapters I had assigned my students looking for key symbols, descriptions, or dialogue, and then in class that day I would be sure we properly made our way through all the moments of the book I deemed important. Like most teachers, at some point along the journey, I realized how vital it is to hand this work over to the students. The first selfish reason being that if I only give the students everything I know I'm not growing; I'm not learning from what they have to offer. Secondly, we also know that the cognitive wrestling is where the learning takes place. If we are doing all the smart stuff before we get into the classroom, what is left for the students? And are we teachers really that smart?