When I first started teaching literature, I felt I needed to cover all the important material in a book. Before class, I would read through the chapters I had assigned my students looking for key symbols, descriptions, or dialogue, and then in class that day I would be sure we properly made our way through all the moments of the book I deemed important. Like most teachers, at some point along the journey, I realized how vital it is to hand this work over to the students. The first selfish reason being that if I only give the students everything I know I'm not growing; I'm not learning from what they have to offer. Secondly, we also know that the cognitive wrestling is where the learning takes place. If we are doing all the smart stuff before we get into the classroom, what is left for the students? And are we teachers really that smart?

When I first started teaching literature, I felt I needed to cover all the important material in a book. Before class, I would read through the chapters I had assigned my students looking for key symbols, descriptions, or dialogue, and then in class that day I would be sure we properly made our way through all the moments of the book I deemed important. Like most teachers, at some point along the journey, I realized how vital it is to hand this work over to the students. The first selfish reason being that if I only give the students everything I know I'm not growing; I'm not learning from what they have to offer. Secondly, we also know that the cognitive wrestling is where the learning takes place. If we are doing all the smart stuff before we get into the classroom, what is left for the students? And are we teachers really that smart?

Somewhere along the way in graduate school I read Russian psychologist Vygotsky's Thought and Language, or at least a couple of paragraphs of it. Vygotsky developed something called the Zone of Proximal Development. The Zone defines how much we can learn when we work with someone who knows more than we do. There is a limit to our colleague's knowledge, so we can only learn up to a certain point, but the zone defines how much we can learn from our colleague when we enter a place of mutual learning. When I began thinking this way in my teaching, things began to get messier. Because I began to really listen, I became more impressed by how intelligent my students actually were. They inevitably came up with startlingly fresh interpretations, ideas, and they related literature to their personal experiences. I began to have realizations about the texts we were reading as I saw them vigorously alive in the eyes of my students. Maxine Greene describes the classroom I was aiming for when she writes,

In my view, the classroom situation most provocative of thoughtfulness and critical consciousness is the one in which teachers and learners find themselves conducting a kind of collaborative search, each from her or his lived situation.

When teaching literature, how then do we go about this collaborative search with our students? At Habla, to explore the diverse interpretations in the classroom we've recently been using a structure we developed called Interpretation Circles. At its core, it's based on Paulo Freire's literacy circles he piloted in Brazil. In a literacy circle there is no teacher, only a facilitator from the community who helps the students to learn written words to describe their world. Recently I visited Sao Paulo, Brazil, and went to an organization that has adapted this idea and named it Circulos de Leitura (Reading Circles). Every Saturday students visit an old house in the center of the city. They sit in comfortable chairs and read books from various authors including Dostoevsky and Shakespeare. They then return to their respective schools and become the facilitators, leading their own Reading Circles. Watch the a video below (in Portuguese):

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCUi78DuD8Q&fs=1&hl=en_US]

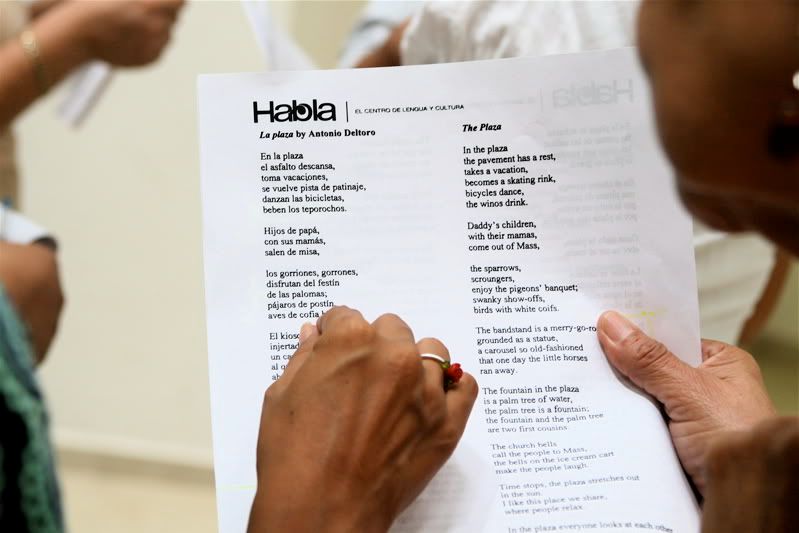

One of our teachers at Habla, Jessica Robertson, introduced me to a discussion structure she adapted from the book Open Minds to Equality published by Rethinking Schools. We applied the structure to literature and named it Interpretation Circles. I recently led a professional development session for public school teachers demonstrating how to use Interpretation Circles in the classroom. Together we first read the difficult poem by Octavio Paz, "The Spoken Word." After reading the poem for the first time, the teachers felt like their students often feel, a bit confused regarding what the poem is about. We explained that there is not one right interpretation for this poem, or any poem for that matter. However, we can arrive at a deeper understanding of what the various possible interpretations of the poem might be through our mutual exploration of the words on the page by engaging in the following process.

Interpretation Circles: A Process

1. Use Interpretation Circles with any texts -- novels, short stories, or poems. Ask the students to reread a section of the text and instruct them to do one of the following. Choose a sentence of phrase from the text that

- they think is most critical for understanding the text. What do they think is most important?

- they are confused by. Where do they need the most help?

- they personally connect to. What resonates with them?

- paints the clearest image. Where do they see images from the text in their heads?

2. Take the students into an open space and gather in a circle.

3. Have the students count off, 1,2,1,2 all around the circle.

4. Ask the 2s to step into the middle of the circle and then turn around facing the 1s. Each person should be looking at a partner. (If there is an extra person, form one group of three).

5. Explain that when you say "go" each person will share the line or phrase they selected and the pair should have a shared conversation about that phrase. If you are focusing on areas of confusion, ask them to work together to figure it out. Then they will look at the other person's phrase and have a conversation about the second phrase.

6. They will now "steal" their partner's phrase.

7. The outer circle moves one to the right.

8. Continue with the process but now discussing the previous partner's stolen phrases. (This allows for each person to discuss new phrases throughout the process. The students are not always sharing their own.)

9. When everyone returns to the classroom, lead a discussion about what the students learned from each other. The air should at this point be thick with ideas.

10. After the conversation the teacher might ask the students to select a key line or phrase and write about their understanding of it in relation to the larger text.

If a free space isn't available, students can sit in the classroom and continuously change partners for each conversation. When Interpretation Circles work at their best, the classroom hums with conversations and the teacher stands on the side . . . listening and learning.