Since, however, you walk

through the streets so straight,

you are courageous, without fault.

- Gabriela Mistral

This is the story of a group of courageous children in Cholul—a small town in Mexico where we live. With the recent student-driven “March for Our Lives” movement, we see young people organizing to try to make the world a better place. Yes, standing up, speaking, and protesting for a better world is a courageous act, but courage can take many forms.

In the midst of all the hustle and bustle of the town square in Cholul, there is a door on one of the adjacent walls labeled Educate. Much like the wardrobe in the C.S. Lewis books or Alice’s hole in the ground, this doorway leads to a magical place. In a small classroom, filled with only desks and chairs, children gather after school several days of the week. One of the classes offered here is Text and Movement, a class created by our lab school, Habla, combining the arts with literacy development.

Led by teachers Madeline Beath and Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri, the class explored the essential question, “Who am I in my community?” Every day the teachers posted a question on the board for the students to respond to in their journals when they came in the room. For instance, one question was, “What is your favorite place in Cholul?” Other questions included:

- What are traditions and holidays you celebrate in your family?

- What myths and legends do you know?

- If someone were to visit Cholul, what would you show them?

- What do you think is underneath Cholul? (The Yucatan peninsula is on a thin layer of limestone—underneath are caves, rivers, and underground watering holes called cenotes, which were believed by the Maya to be passages to the underworld.)

These questions led to conversations about favorite parts of the city, traditions, and how they are celebrated in families, and a classroom exploration of Mayan and Yucatecan myths and legends. Students created a map of the city from their own point-of-view. Their teacher Madeline explained, “They don’t think about the 7-Eleven or the market—those places don’t have any meaning for them. Their Cholul is their house and the public spaces where they see their friends.”

The teachers then introduced students to the bilingual book, My Name is Gabriela: The Life of Gabriela Mistral / Me llama Gabriela: la vida de Gabriela Mistral by Monica Brown and John Parra. It is a biography of Gabriela Mistral, the first Latin American writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tommaso reads Me llamo Gabriela to the students. Photography by Madeline Beath.

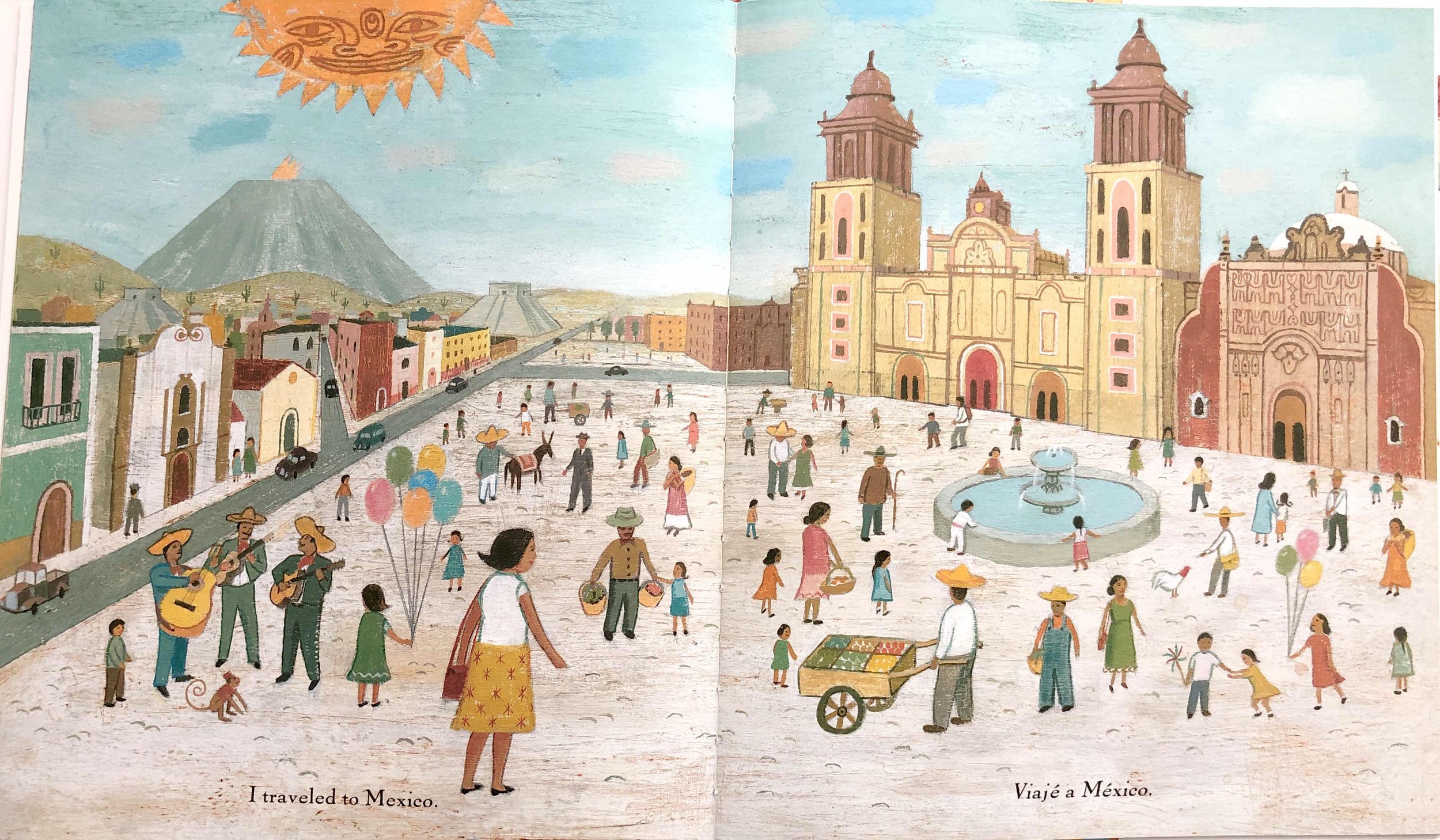

Born in Chile, Gabriela visits many places around the world and this is highlighted with the phrase “I traveled to/Viajé a” with an image of the featured place on each page.

- I traveled to Europe—to France and Italy

- I traveled to Mexico

- I traveled to the United States.

The teachers asked the students the question, “What if Gabriela came to visit you here in Cholul? What would we show her?”

The students began to draw and describe their favorite buildings and sights in Cholul. They drew their houses, the cathedral in the middle of town, carnival tents, amusement park rides, and the park. They also drew pictures from nature: birds, the sun, the and the cenote's entrance in the town square.

Stefany writes about her town, Cholul. Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

Luis talks about his favorite places in Cholul. Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

In the main town square of Cholul, there was a large white wall extending about 150 ft. The students spend much of their time in front of this wall playing soccer or basketball, participating in community and school events, or just hanging out with their friends. The students asked if they could recreate their drawings on the white wall. Tommaso, a visual artist himself, emphasized the importance of creating a mural that would be cohesive and aesthetically beautiful. The students began to imagine what a colorful mural in their town might look like and what it would take to accomplish it.

The white wall. Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestre

Tommaso scanned the students' drawings and combined them into a horizontal landscape of the city. Every image was drawn by the children.

Click on image to enlarge.

Next they had to clean up and repair the wall. Tommaso explained, “At that point there were a lot of weeds that needed to be cut down and the holes needed to be fixed.”

Over the course of the next few weeks, with the help of some visiting high school students, the students from Cholul painted their mural. All of the younger students learned about color theory and mixing colors and they created the sequence of colors that spanned the wall, from sunrise to sunset.

Painting colors from sunrise to sunset. Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

The high school students traced the younger students’ drawings of buildings on the wall with pencil (recreating the smaller Photoshop version of the mural). Then, the younger students painted the buildings choosing their own colors.

Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri

When I visited and saw the children transforming the wall of the town square, I thought about Gabriela Mistral's first job as a teacher. While she was teaching she was also writing. One of her most powerful poems about children is Su nombre es hoy,

"Many things can wait. Children cannot. Today their bones are being formed, their blood is being made, their senses are being developed. To them we cannot say 'tomorrow.' Their name is today."

Photo by Tommaso Iskra de Silvestri