In Providence, Rhode Island, a group of colleagues and I started the ArtsLiteracy Project, an organization that explored ways of teaching reading and writing primarily through performance. We partnered directors and performers from local theatres with English and language teachers in schools, and together we developed a methodology for using performance to teach reading. As our handbook reveals, in Providence we were principally concerned with getting students up on their feet and performing.

In Providence, Rhode Island, a group of colleagues and I started the ArtsLiteracy Project, an organization that explored ways of teaching reading and writing primarily through performance. We partnered directors and performers from local theatres with English and language teachers in schools, and together we developed a methodology for using performance to teach reading. As our handbook reveals, in Providence we were principally concerned with getting students up on their feet and performing.

Three years ago I moved to Mexico to open Habla: The Center for Language and Culture in Merida, Yucatan. Merida is a culturally rich city, but it has almost no formal theater groups. However, many talented visual artists live in this city. In collaboration with many of these artists, we continued experimenting with ways linking the arts to language but now with a greater emphasis on the visual arts rather than the performing arts. Recently we led a series of professional development workshops for teachers who taught in the most economically disadvantaged schools in the city, an area called Emiliano Zapata Sur. We were helping teachers find ways to teach students to read and write who have very low literacy levels. What follows is a description of the theory and practice of moving from the word to the image.

From Text to Image: A Theoretical Framework

One of the primary influences in my literacy work is the late Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Working with the rural and urban economically poor in Brazil, Freire created literacy circles taught by members of the community. The teaching methodology of the literacy circle consisted of showing images of daily life in Brazil, and then asking the students to find the words to describe the images. The words and the image worked symbiotically. Since Freire was working with students who couldn't read, he found that beginning with images from the world of the students rather than the words they were unfamiliar with was a natural starting point.

Although I'm a firm believer in the ideas and philosophies behind arts-integration, I've never fully accepted the concept or the term. As Freire demonstrated, there is not a separation between the image and the word, they live in solidarity. The London Group describes the modern world we live in as one of multiliteracies. When we need to communicate, we use all the symbol systems within our grasp. This is particularly true in the age of the internet where image, text, sound, video all work in tandem to communicate a message. In an age of multiliteracies, arts-integration isn't an option for the creative teacher: it is a necessity for all teachers of all subject areas. So perhaps the questions we should be asking isn't how can we integrate the arts into the classroom, but rather how can students take meaning from and make meaning with multiple symbol systems? How can we create classroom environments that are multiliterate spaces? These questions take us to the core of why it is crucial to make the arts a daily part of life in schools: to develop citizens who can think and communicate clearly, not just orally and textually, but with as many tools as are available in the global toolbox.

The Context

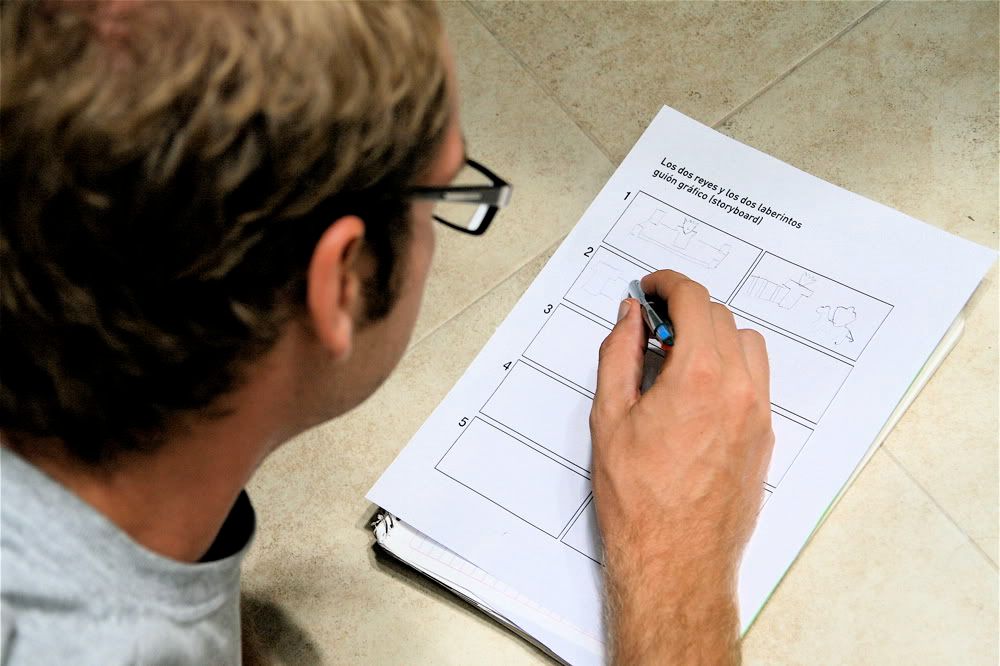

On a warm Saturday in Mexico, forty-two teachers from public schools around the city of Merida gathered at Habla to participate in a workshop called, "Reading Beneath the Surface - Teaching Comprehension." Our goal was to examine with the teachers the question, "What does it mean to reach a deep understanding of text?" and to challenge the way literature is often taught at a surface level with cursory examination of vocabulary, setting, plot, and character. We participated in a variety of activities over the course of the day reading and analyzing the story "Los dos reyes y los dos labyrintos" (The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths) by Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges. We had extended discussion about the story, using interpretation circles described in detail in a previous article on this site. After the participants read and discussed the story, teaching artist Karla Hernando and I wanted to experiment with different ways we could help students interpret the story through imagery.

Comprehending through Image

With Freire's work with words and images in mind, we wanted the teachers to see how it might be possible to interpret text not only through discussion and writing, but also by recreating the text through a visual symbol system. After reading and discussing Borge's story in an interpretation circle, we gave the participants a black piece of paper. We asked the participants to cut out symbols representing the different parts of the story: the characters, the objects, and the setting. When they finished cutting out their symbols, they used the cutouts to tell the entire story to each other in groups, without reading directly from the text. They needed to then remember the events of the story and retell them with their symbolic cutouts in a way that captured the attention of the other group members. The idea of telling stories from cutouts was inspired by Jeffrey Wilhelm’s symbolic story representations described in his book You Gotta BE the Book.

We learned about using symbolic icons in the classroom from CAPE creative director Arnold Aprill and Chicago artist Bernard Williams. Icons are simple one-dimensional abstract representations of people, places, things, or ideas. To create icons students only need scissors, paper, and pencils. It's actually better if they don't draw on their icons at all. They simply cut the silhouette of the icon out of the paper. Icons allow us to move from the concrete directly to abstract, symbolic representation. In Borge's story of the two kings, one king might be represented by a triangle and the other by a square. (Click here to download a process for using symbolic icons with any subject area.)

Books as Art Objects

As we move increasingly to digital books with the proliferation of Kindles and iPads, we begin to be more conscious of what the special qualities are of holding a book as object in our hands. There has been a growing movement around the world of creating and curating books as art objects. Over the last year we've had several artists visit Habla--including Robert Possehl, Amanda Lichtenstein, William Estrada, and Cynthia Weiss--who have presented a variety of ways for students in the classroom to make their own books. Bookmaking in education reflects the work that is being done in several centers around the world dedicated to collecting and displaying books as art objects including the Center for Book Arts and the Jaffe Center for Book Arts.

Since the teachers had already told their stories using icons, the next step was to design a book that retold the Borge's story, but only with icons and other visual images. Most of the people in the room didn't consider themselves artists, so we wanted to give them some structures which would help them all engage in a fruitful process resulting in compelling products. Here were the guidelines teaching artist Karla Hernando and I designed:

1. No words. Our goal was to move the participants to a higher level of abstraction. By omitting words, the teachers needed to translate from the words of the text to the image on a page. This necessarily required them to understand the story deeply in order to retell it using only images.

2. No human figures. We've found that participants’ default settings in the visual arts are often stick figures or a similar representation. We wanted to push the teachers to think in design terms that are more abstract, using shapes to move the story forward.

3. 40-40-20. One of the primary principles we'd learned from various teaching artists is to limit the color palette of the materials. One of the initial instincts of a teacher with little artistic background might be to give the students all the colors available, offering them boxes of crayons and stacks of construction paper. We've learned the importance of offering the students only a few colors, limiting the palette before the project actually begins. Karla chose to give the teachers only four colors of paper, and she explained, "Choose two colors as your primary colors to use for most of your book; these colors should be 80% of the book. Then use one or two more colors for emphasis, but these should be only about 20% of the book. These should be the colors that surprise you when you see them."

4. 5 pieces of paper. We only had about 90 minutes to complete the project, so we wanted to keep the books small. There is a great advantage to limiting the size and scope of any creative project in the classroom. For students intimidated by art making, setting limits helps them see that the project is doable and not overwhelming.

Participants first planned their books using storyboards. Then after 90 minutes of working on their books Karla showed how they might bind them with a piece of string (holes were punched in all the pieces of paper so it was quite easy to run a string through them to fasten them.) To document the final products, we filmed teachers flipping through their books. See the results below.

[flickr video=5162119519 secret=d9127fd403 w=400 h=300]