Previously published here on the Harvard Graduate School of Education blog, "Voices in Education."

Many years ago when I was a student in a teacher certification program, one of our daily requirements was to observe the classroom of a different teacher in the school. Many of my colleagues complained about this assignment—sitting in someone else’s class when you have papers to write, hundreds of pages to read each week, and your own class to teach can seem like a waste of time—but for me this was the most important part of the program. I did my student teaching in a large urban high school, and, like any public school, it had a handful of teachers who were in my view exceptional, many that were fine, and a few that probably needed to be in another profession. I observed them all.

It’s obvious that a young teacher has much to gain by watching an excellent teacher, but what is there to learn from an average or even poor one? I challenged myself to learn one thing that I could incorporate into my own practice from every teacher. When I walked into Nancy’s room, a biology teacher in an urban high school, I immediately noticed the aesthetic beauty of the space: lush aquariums along the windows, lab spaces for the students with all of the proper equipment in place, and a multi-colored agenda of what the day’s work would be. On her agenda the words “lab report” were surrounded with an illustration of an explosion like the “BAM!” in a Batman comic book. When she began the class she announced, “The lab report is your chance to express your ideas, to tell everyone what you’ve learned. You want to convey that ‘aha’ moment to the rest of us.” Today, I still begin my classes with an agenda, and more importantly, I hope I convey the same enthusiasm about my students’ work that Nancy did.

Throughout my now twenty years in the field of education, whenever I have sat in a classroom (whether to coach new teachers or to participate in a professional development workshop offered by a colleague), I have always entered the experience with anticipation. Rather than thinking only of what I can offer as an experienced teacher or, worse, having an “I’ve seen it all before” attitude, I ask, “What stories does this classroom have to tell? What can I learn to incorporate into my own practice?” I approach every experience in my fellow teachers’ classes with a sense of inquiry, and this makes my time spent in educational spaces invigorating because I always have more to learn.

In the last few years, as I wrote the book A Reason to Read: Linking Literacy and the Arts, my colleague Eileen Landay and I applied this approach to writing about education. When we visited schools, sat in classrooms, or taught our own students, we looked for the stories that each group of teachers and students had to tell. Each chapter of the book begins with one of these stories—Flor, who endlessly drew pictures of birds in her English classroom in Mexico; Russell, who wrapped himself up in a stage curtain and wouldn’t come out; Daniel and his students in Brazil, who organized a peace demonstration in their small town of Inhumas.

Stories of success describing real teachers and students provide us with multi-dimensional portraits of what life is like in the rough-and-tumble world of schools, capturing both the beauty and challenges of teaching and learning. As teachers we are inundated by seemingly endless top-down mandates that tell us what we ought to be teaching. What we need much more of is time for teachers to observe and have conversations about each other’s practice. At the policy level we need to dedicate fewer resources to educational experts sitting in rooms developing lists of standards and tests and more toward discovering what inspirational on-the-ground teaching looks like. When Malcolm Gladwell was asked where story ideas for his influential books like The Tipping Point and Outliers came from, he answered that he doesn’t write about famous people or those who hold all the power. He said, “You don’t start at the top if you want to find the story.” The stories that we need to find and tell live in our classrooms. They reside in the daily interaction of students and teachers. If we are to find ways to transform our schools, we must spend more time in our fellow teachers’ classrooms working to understand these stories of true educational change.

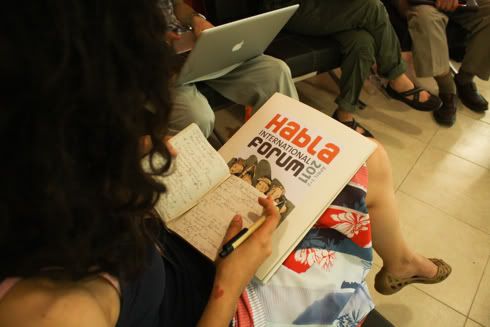

Since my years first as a student and then as a teacher, I always have had the feeling that summer is a time for rest and relaxation. However, in the years since I was the director of The ArtsLiteracy Project and then of Habla, summer has been the busiest time of the year. In the summer we work with teachers from around the world who are on their vacations but still eager to join other educators in sharing ideas and developing in their teaching practices. I do teach during the year as well, but summer for me is a time to offer what I've learned to other educators and to learn from them in return.

Since my years first as a student and then as a teacher, I always have had the feeling that summer is a time for rest and relaxation. However, in the years since I was the director of The ArtsLiteracy Project and then of Habla, summer has been the busiest time of the year. In the summer we work with teachers from around the world who are on their vacations but still eager to join other educators in sharing ideas and developing in their teaching practices. I do teach during the year as well, but summer for me is a time to offer what I've learned to other educators and to learn from them in return.

Last year we were sitting in a staff meeting at our school Habla discussing how we might better induct new teachers into the culture of the school. This quickly led to the question, "What exactly is the culture of Habla? How would we put it into words?" Over the years I've seen how policy makers and education leaders think they might create a shared culture by developing lists of standards or principles or by publishing documents that they think will influence teachers' practices in the classroom. Many of these well-meaning attempts burden teachers with a labyrinth of documents that seem to have little application to the classroom. However, in some cases when these frameworks are straightforward--like

Last year we were sitting in a staff meeting at our school Habla discussing how we might better induct new teachers into the culture of the school. This quickly led to the question, "What exactly is the culture of Habla? How would we put it into words?" Over the years I've seen how policy makers and education leaders think they might create a shared culture by developing lists of standards or principles or by publishing documents that they think will influence teachers' practices in the classroom. Many of these well-meaning attempts burden teachers with a labyrinth of documents that seem to have little application to the classroom. However, in some cases when these frameworks are straightforward--like